|

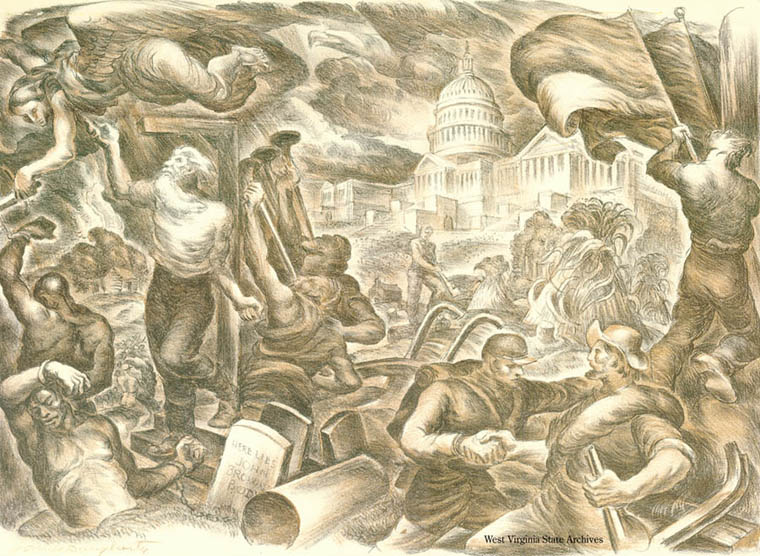

In the century and a half since his execution, John Brown has been debated, discussed, celebrated and condemned. Beginning in 1859, John Brown has been the subject of numerous theater productions, books and articles, songs, paintings and other artwork that have portrayed him variously as a hero or villain, as a martyr or madman. Some of the more memorable portrayals include Thomas Hovendon's painting depicting John Brown stooping to kiss an African American child (1884), Stephen Vincent Benet's Pulitzer prizewinning epic poem "John Brown's Body" (1928), John Steuart Curry's controversial mural in the Kansas statehouse of a dominating John Brown (1937-40), and Warner Brothers Santa Fe Trail with a villainous John Brown (1940). |  |

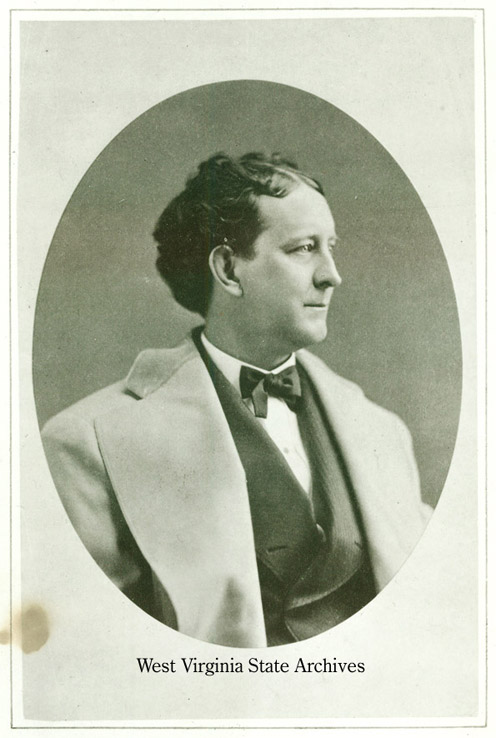

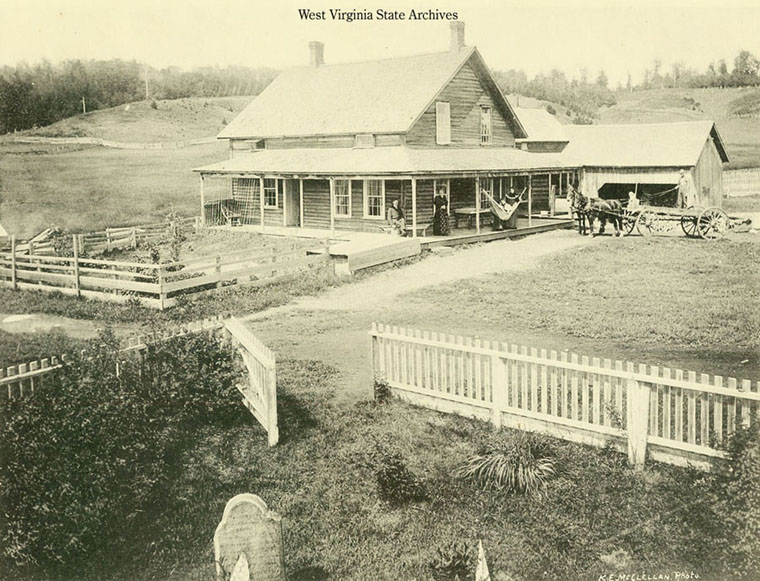

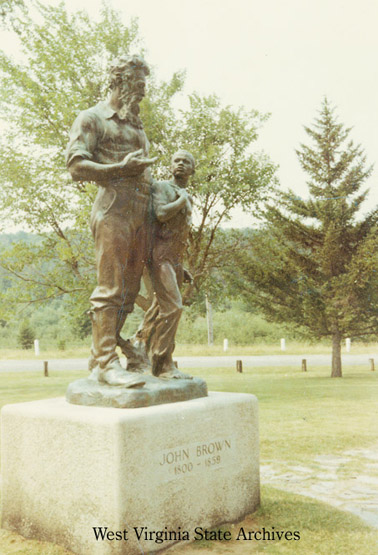

While popular in print, on stage and the screen, and in art, John Brown also has generated a number of commemorate, preservation, and tourist activities. Perhaps the earliest effort was at North Elba, New York, in 1870, when journalist and lecturer Kate Field and others purchased the farm with the idea of preserving it. In 1896, the property was deeded to the State of New York. The John Brown Memorial Association, a largely black organization with chapters in several cities, formed in 1922 and held an annual pilgrimage to the North Elba farm for many years. Through the association's efforts, a statue of John Brown standing with an African American boy was erected in 1935.

|

|

pilgrimage to North Elba, May 1930 |

by Pollia, at North Elba |

|

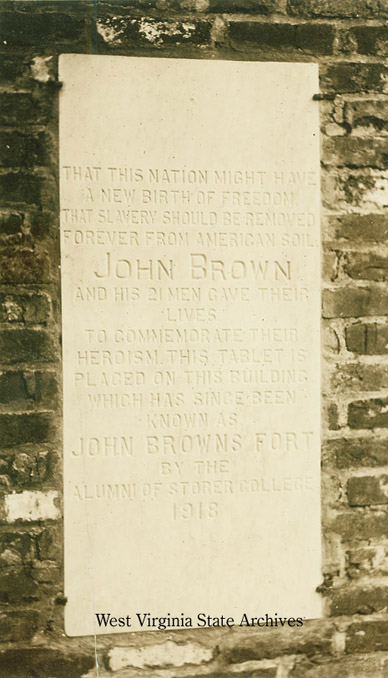

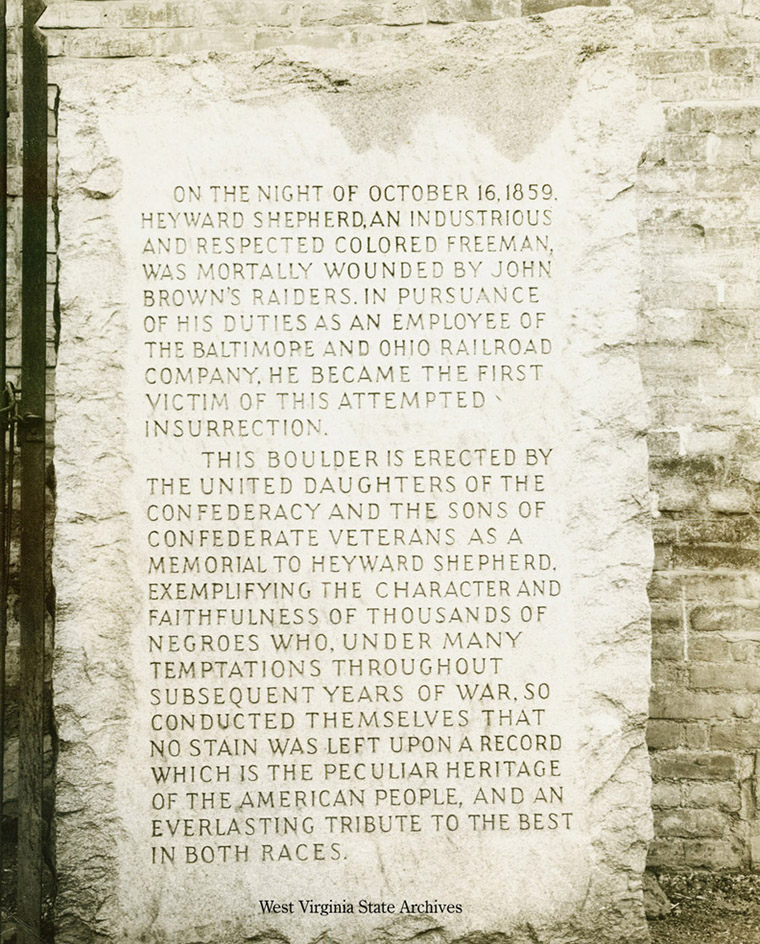

A dozen years earlier, the Niagara Movement, a short-lived African American civil rights organization, had chosen Harpers Ferry for its first public meeting because of John Brown. Devoting an entire day to a celebration of Brown, attendees listened to speeches on the man and made a pilgrimage to John Brown's Fort. Though disavowing the raid's violence, W. E. B. Du Bois affirmed a belief in John Brown. "And here on the scene of John Brown's martyrdom," he proclaimed, "we reconsecrate ourselves, our honor, our property to the final emancipation of the race which John Brown died to make free." Nearly two decades later, in 1932, Du Bois wrote the text for a tablet the NAACP tried unsuccessfully to place in Harpers Ferry in memory of John Brown. (In 2006, the NAACP placed a tablet with the wording of the 1932 tablet on the Storer College campus.) John Brown's legacy in Harpers Ferry has not been the exclusive property of his admirers, however. Local critics in the decades after the raid often pointed to the raid's first casualty, African American Heyward Shepherd, a railroad employee at Harpers Ferry, to argue the false premise of Brown's raid. Representing this view, the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Sons of Confederate Veterans placed the Heyward Shepherd Memorial in Harpers Ferry in 1931. |

|

John Brown continues to attract interest. During the sesquicentennial year in 2009 of his raid on Harpers Ferry, events were held in the 4-state area around Harpers Ferry, as well as in Ohio, New York and other places connected to his life. Included were a number of seminars, dramatic performances, tours, and exhibitions on Brown and his legacy. Several new books and articles on John Brown also were published in 2009. Yet, in some ways, John Brown remains an enigma even after decades of serious scholarly study. And his actions remain the subject of debate, fueled in recent years by comparisons with homegrown and international terrorists. Was John Brown a villain? Or, was he a hero? The answer depends, as it has since the late hours of October 16, 1859, on an individual's perspective.

"Was John Brown simply an episode, or was he an eternal truth? And if a truth, how speaks that truth to-day? John Brown loved his neighbor as himself. He could not endure therefore to see his neighbor, poor, unfortunate or oppressed. . . .This is the situation to-day. Has John Brown no message:no legacy, then, . . .? He has and it is this great word: the cost of liberty is less than the price of repression." - W. E. B. Du Bois, John Brown, 1909.

"John Brown will live in history; but his name will not be found among the names of those who have wrought for humanity and for righteousness; or among the names of the martyrs and the saints who 'washed their robes and made them white in the blood of the Lamb.''Yet Shall He Live': but it will be as a soldier of fortune, an adventurer. . . ." - Hill Peebles Wilson, John Brown Soldier of Fortune: A Critique, 1913.

Play, Ossawattomie Brown or The Insurrection at Harpers Ferry, by Mrs. J. C. Swayze. 1859

Sheet Music, John Brown Song (W. W. Patton lyrics, 1861)

Speech, Frederick Douglass on John Brown, Given at Storer College, 1881

Letter, A. J. Holmes to Messrs. Roberts Brothers, August 16, 1892

Invitation, John Brown Memorial Park dedication, Osawatomie, Kansas, 1910

Flier, John Brown Memorial Association picnic, June 30, 1928

Clipping, New York Herald Tribune, May 10, 1935

Clipping, Osawatomie Graphic, May 16, 1935

Bill, Creation of John Brown Military Park, 1935

Letter, J. Walter Coleman to Boyd B. Stutler, October 1, 1951

Clipping, New York Times, October 4, 1959

Speech, Boyd B. Stutler at John Brown Raid Centennial, October 16, 1959

Program, Governor's Day, John Brown Raid Centennial, October 17, 1959

Manuscript, "The John Brown Song," by Boyd B. Stutler

"John Brown's Fort," by Clarence S. Gee (West Virginia History, Vol. 19)

"The Historical Authenticity of John Brown's Raid in Stephen Vincent Benet's 'John Brown's Body"," by Mary Lynn Richardson (West Virginia History, Vol. 24)

"An 'Ever Present Bone of Contention': The Heyward Shepherd Memorial," by Mary Johnson (West Virginia History, Vol. 56)