West Virginia & Regional History Center, used with permission

Remember...

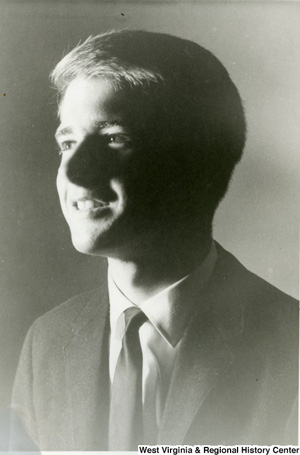

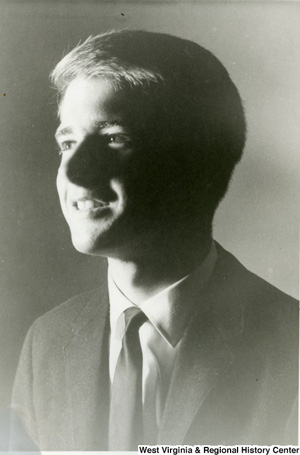

Thomas William Bennett

1947-1969

"Mankind must put an end to war before war puts an end to mankind."

John F. Kennedy

West Virginia & Regional History Center, used with permission |

Remember...Thomas William Bennett

|

Thomas William Bennett was born on April 7, 1947, in Morgantown, West Virginia, to Gale M. Miller Bennett and Thurman Lee Bennett. According to the 1940 Federal Census, the family lived on Hillside Drive, with Mr. Bennett's brother Robert. Mr. Bennett was a foreman for the electric company. All of the family had been born in Wheeling.

By 1952, the family lived on Junior Avenue. Mr. Bennett died of Hodgkin's disease that year, leaving Mrs. Bennett and three sons, George, James, and Thomas. Mrs. Bennett remarried, to Kermit Gray.

Thomas Bennett was on academic probation by 1968, and with the loss of protection granted by his academic status, he became exposed to the draft. Many of his friends had already signed up or been drafted and gone to war, including high school friend David Kovac. According to Edward F. Murphy, in his article for Vietnam magazine, "A Conscientious Objector's Medal of Honor," the loss of David Kovac, who died in Vietnam in 1965, honoring his friend's memory was an influence upon Thomas Bennett's decision to go as a conscientious objector. ("A Conscientious Objector's Medal of Honor," History.net, accessed 21 March 2018, http://www.historynet.com/a-conscientious-objectors-medal-of-honor.htm.) Thomas registered as a conscientious objector who was willing to serve. Though no connection could be found between the two, the likeness between Bennett's case and that of World War II soldier Desmond Doss is apparent. Doss, as a Seventh Day Adventist, could not serve in a capacity which would cause him to kill a person. He set an example of how to serve both faith and country when he successfully petitioned to serve as a field medic, an unarmed position. Similarly, though raised as a Baptist, Thomas Bennett approached his duty with help from a recruitment specialist. He entered service in Fairmont, West Virginia, in 1968 and was off to Fort Sam Houston for medic training. Before leaving for Vietnam, he wrote a prayer, which was oft repeated in articles about him after his death:

Oh, God, shake me from my apathy.

From my wanderings of mind.

Create in me discipline, concern, and love.

Help me live:really live:in Spirit and the Truth.

As those around him would soon see, this prayer was the embodiment of Thomas Bennett. Thomas Bennett began writing letters and creating audiotapes to send home nearly as soon as he'd left Morgantown. During basic training and in the airport in San Francisco from which he'd leave for Vietnam, he included strangers on the audiotapes in interviews. In his letters, he described in detail what he saw, what beginning life in the military was like, what he did that day, whom he met, and his view on religion and philosophy of service. His accounts offer an inside look of not only military life but of the struggles inside his head and heart as he made his way to war. He told himself and the recipients of his mail that it was unlikely he'd become involved in combat because he'd be behind the front lines and his status as a medic would make it less likely that he'd be put directly in harm's way.

Examples of the writings of Thomas Bennett extracted below are taken from letters in the Morgantown Dominion News (March 29, 1970); letters and transcripts made by Bonni McKeown of audiotapes A&M 2714; and Thomas W. Bennett (1947-1969) Papers, West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries:

On January 2, 1966, Thomas Bennett wrote home to his parents a letter containing the following passage:

I would be able to if I believed one of the most optimistic of all sayings:"God's in his heaven. All's right with the world." I don't believe that though because another way of saying it is "God's in his heaven, there's nothing wrong with the world." I don't think that's true. I think a better way to express the thought is "God's in his heaven, there's hope for the world." This I believe.

It's unclear the occasion and from where this letter was written since he was still in school in 1966, but it is an excellent example of the type of philosophical thinking and reflections that appeared in his letters throughout his correspondence. In other letters, Thomas Bennett alludes to his travels, so he seems to have had other excursions out of Morgantown and away from home.

In January 1969 in Vietnam, he wrote to his parents that he'd been assigned to Company B and the next day, he was scheduled for a helicopter ride out to meet his new unit. Quoting, in part, 1 Corinthians 13:11, he writes, "Tomorrow, my Journey begins. 'But when I became a man, I put away childish things..' God help me. Love, Tom" (Weirton Times, 24 March 1970, p. 4.) His letters frequently ended with the word PEACE written in capital letters at the bottom of the page. About patriotism, he writes, "I will continue to serve my country within the limits of my personal conscience until I feel there is no longer any hope. At this point I feel there is plenty of hope for changes and for America," concluding, "I'll stick with her." (David Milne, "Kunsler.Calm, Jocular, Predicting," Morgantown Dominion Post, 4 April 1970, p. 9B.) But he was also aware of what patriotism could mean, writing, "I will go and possibly die for a cause I vehemently disagree with." (Morgantown Dominion Post, 29 March 1970, p. 6A.)

Thomas Bennett's tour in Vietnam began on January 6, 1969. While trained as a medic, he also took shifts on perimeter patrol or "listening patrol." He referred to it as listening patrol because it was so dark at night that no one could see very far, so they listened for odd noises that might betray an enemy location. He wrote home that he had not yet picked up a gun since deployment. In his letters home, he describes the other men in his unit, new friends, and the new routines of his day. Sometimes quiet, sometimes explosions were near, sometimes sleepless nights, he described all in his audiotapes and letters. Early on in his letter-writing, he was enthusiastic, optimistic, and expanding into his new roles. A new nickname was pinned to him. In school, he'd been voted "Most Polite." In January 1969, he was called "Doc." He wrote about the cases that he treated. He liked to check on his patients, to ask about the job each man was doing. He wrote about the type of medical care he was asked to render, including treatment for sunburns, cuts, and a rat bite. He was encouraged that the men were seeking him out, coming to him from other units. According to Edward Murphy, writing for Vietnam magazine, he'd written home that he intended to study medicine when he returned. ("A Conscientious Objector's Medal of Honor," History.net, accessed 21 March 2018, http://www.historynet.com/a-conscientious-objectors-medal-of-honor.htm.)

The excitement of his military experience changed when the 14th deployed to Chu Pa. They had to climb a mountain. Thomas Bennett described the task at hand in his letters home. The mountain was very steep, and each man was carrying as much as he possibly could. Bennett watched as one man pulled a groin muscle and couldn't go on. Without a word, the men of the unit picked up the injured man's equipment and also carried him. Thomas Bennett writes in January 1969, "The guys were beautiful. It chokes me up to think about it" and "War is a terrible thing. I HATE it. Yet it seems to bring out the best [in] these men. Now that we've made it to the top, there is very little danger." Many suffered various aches, pains, or injuries on the way up the mountain. For Thomas Bennett, who was 5' 6" and slight, this was quite an accomplishment. ("A Conscientious Objector's Medal of Honor," History.net, accessed 21 March 2018, http://www.historynet.com/a-conscientious-objectors-medal-of-honor.htm.)

Fred Hutchinson, in his letter to WVU officials regarding the service of Thomas Bennett, describes the terrain in Chu Pa and the events there:

A brief comment about the terrain of the Chu Pa. My recollection is that the diameter of the base of the mountain was about 6-8 miles across, the highest of the many peaks was some 2000 feet above sea level, it was densely forested with thick undergrowth on most sides of the complex, many rocky cliffs and steep slopes, and dark under that canopy. The mountain top, in that season, was wreathed in mist and fog until mid-morning. There usually was fog around the base, especially on the two sides bounded by a river until mid-morning. It was an impressive piece of terrain even to a West Virginia Mountaineer. A poet probably would have termed it "dark and menacing," had one been there at that time. ("1st Battalion, 14th Infantry Regiment: Golden Dragons," accessed 21 March 2018, http://1-14th.com/Vietnam/Timeline/tv_68_Hutchinson_letter.html.)

On January 24, 1969, Thomas Bennett made an audiotape. In it he speaks of the military life and what he was seeing:

In honesty, I guess I could say it sorta makes me sick sometimes, the whole thing.. My one impression so far, is disbelief.. I just can't believe this stuff is going on. So that's that. But it's kind of funny actually, I'm dirtier right now than I've been in my whole life. And I'm farther from home than I've been in my whole life. I'm learning more, faster probably than I've ever learned. And, of course, the more you learn, the more you see, and the less concrete everything is in your mind. You begin to see how complex everything really is.

Yet he continued; despite the fear, he was more at ease with himself, and more confident. At the end of the recording, he says,

There are several final things I'd like to emphasize. First of all and foremost, I am still safe. Second, I am ready for death, all the way around, and I'm proud that I'm ready. Third of all, and most important perhaps, how much I really love you.

On the last audiotape home, Thomas Bennett says,

And I want you to understand also that for some reason, right now, I feel:how do I explain it, let's see:I feel that they can't hurt me in any way. I have had and am having such a rich, full, good, exciting life that, well, nobody can take that away from me. It can't be erased or diminished in any way.

A little while later, after downplaying the real danger, he says, "You know, I've had my 21 good years."

The 1st Battalion, 14th Infantry Regiment, known as the Golden Dragons, has a long history as a U.S. fighting force, starting with the Civil War. The regimental motto, "The Right of the Line," has two connotations. One is to the place of honor, and the other to a place in battle where the weak side is defended by a strong protector on the right. The 14th's lineage passes from the Civil War through the Indian Wars, the War with Spain, through World War II and Korea, and into Vietnam. ("14th Infantry Regiment Lineage," Fourteenth Infantry Regiment: 1776-1966, accessed 21 March 2018, http://www.i-kirk.info/14thInfantry/lineage.html#1stBattalionLineage.)

In February of 1969, the 1st Battalion, 14th Infantry, Company B, was in Vietnam, in the region of Chu Pa Mountain. The area had been quiet, but enemy forces were moving in. The 14th was there to patrol, seek out, and vanquish the enemy. Private Thomas Bennett was already with them. The after action report issued by Robert B. Lander, Lieutenant Colonel, Infantry, documents that Company B and Company D were screening a ridge on the west side of Chu Pa Mountain as a two-battalion attack was staged. Company B encountered unexpected terrain in a double canopy jungle. Aerial reconnaissance failed to reveal the steepness of the terrain, the rock faces, and abandoned bunkers and caves. There had been no sign of the enemy. Company B advanced into the rock complex, and, just as they were clearing it, the entire company came under "withering fire" from a ridge to their north. The volley of AK47, machine gun, B-40 rocket, and mortar fire pinned down the company and divided it, but the unit leaders quickly adapted, returned fire, and began reassembling forces together. The enemy fire subsided in the night, and the American forces moved to create a landing zone but failed in the attempt to resupply the ammunition. (Department of the Army, Headquarters, 1st Battalion 14th Infantry, "After Action Report for Chu Pa Mountain Operations, February 11-15, 1969," 25 February 1969, accessed 21 March 2018, http://1-14th.com/Vietnam/Timeline/AAR_6902_ChuPa.html.)

According to the after action report,

On 11 February 1969, Company B, 1st Battalion, 14th Infantry, minus its third platoon, and with the 1st platoon, Company D, 1st Battalion, 14th Infantry attached, was screening a ridge on the western side of the Chu Pa Mountain vicinity, coordinate YA934683. This cross attachment had been necessitated on the day the operation commenced because weather conditions had prevented the repositioning of all the elements of Company B and Company D. As the attack was to be a coordinated two battalion attack, the Commanding Officer, 1st Battalion, 14th Infantry attached the available platoon of Company D to Company B to permit Company B to cross the Line of Departure on time with a maximum amount of combat power.At 1700 hours, just as the two lead platoons and company command group cleared the rock area, the entire company came under withering fire from the ridge to the north.. The company received AK47, machine gun, B-40 rocket and mortar fire from tunnels and bunkers to the northwest, north, and northeast. They were unable to locate the exact positions from which fire was being received because of the dense jungle growth in the area. Additionally, they received automatic weapons fire from the draw to their south. The company estimated that there were at least seven machine guns employed against them.

The initial volley pinned down the company and caused it to be broken up into several separate squad and platoon size elements. During the first few rounds, the artillery forward observer was wounded and knocked unconscious. This phase of the battle consisted of a number of individual actions as the small unit leaders responded to the situation. During this period, all available artillery, air strikes and gun ships were brought in to support the company. The artillery forward observer had regained consciousness and rushed across an open area to an exposed position to direct artillery fire. He brought fires in to within 30 meters of the friendly elements. At least one enemy machine gun took a direct hit as troops saw pieces of the weapon and bodies fly through the air. Nearly 600 rounds of artillery were fired during the first hour of this contact.

On the morning of 12 February 1969, the Commanding Officer of Company B sent out a small patrol about 50 meters west of his perimeter to recover the body of one of the soldiers killed the previous evening. While moving to the area, the patrol saw and killed six North Vietnamese Regulars in the vicinity of some rucksacks that had been dropped by members of the unit during the initial movements of contact. The patrol was forced back to the perimeter by enemy fire. From this time until the company was relieved by Company C and Company D on 15 February, no further small arms fire was received inside the perimeter except when helicopters attempted to land in the Landing Zone cut in the western position. However, the enemy did not withdraw, and Company B could not move from its position without drawing heavy fire from all directions. (This account is shortened from the report to emphasize the events of February 11 and 12. The full report is: Department of the Army, Headquarters, 1st Battalion 14th Infantry, "After Action Report for Chu Pa Mountain Operations, February 11-15, 1969," 25 February 1969, accessed 21 March 2018, http://1-14th.com/Vietnam/Timeline/AAR_6902_ChuPa.html.)

It was on February 11 that Thomas Bennett lost his life. Several eyewitness accounts were written and are linked to the 14th's webpage, which honors him. ("1st Battalion, 14th Infantry: Vietnam: Medal of Honor: Bennett, Thomas W.," accessed 26 March 2018, http://1-14th.com/MOH/MOH_Bennett.html.)

Sergeant McBee wrote that Private First Class Bennett left his place of relative safety, rushed through heavy fire, and rendered aid to troops who had been wounded. He picked up one soldier and carried him to safety. On another rescue mission, Bennett was knocked down by the concussive force of a nearby explosion. McBee added that Bennett got back up, ran to the wounded man, and, though they were in an exposed position, administered aid until the man was stable enough to move. The account continues with similar descriptions regarding three more men, and six more, and then one more. Bennett was advised not to go after the remaining one because of the intensity of small arms fire, but he did not hesitate. When he neared the last wounded man's position, he fell to small arms fire, mortally wounded. The same account is written from Sergeant Tomeo, who'd warned Thomas Bennett that his life was in danger due to the risks he was taking to treat the wounded, but Pfc. Bennett fearlessly kept on. Sergeant Smith wrote that Bennett's selfless actions "inspired all of us and made us determined to defeat the enemy forces. His extreme bravery during the entire period of time was something you would have to observe in order to realize how really courageous he was."

Pfc. Bennett was promoted posthumously to the rank of corporal. In Morgantown, the Bennett and Gray families were told that Thomas Bennett was missing in action. The next week, their worst fears were realized with the confirmation that Thomas Bennett had been killed in action. The announcement appeared in the Morgantown Dominion News and the Fairmont Times, but there was no mention of how he died. That would become better known in the coming year. Several West Virginia papers carried the news that Thomas Bennett would be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor in 1970. In honor of the event and in memory of such an extraordinary young man, the Dominion Post ran an article about him that included letters he'd written home. (29 March 1970.) The medal would be received by his mother, with her family, from President Richard Nixon on Thomas Bennett's birthday, April 7, 1970.

The Medal of Honor dates to 1861 for Navy veterans and 1862 for Army veterans and is the highest award for valor available for military men and women. (Congressional Medal of Honor Society, "The Medal of Honor," accessed 29 March 2018, http://www.cmohs.org/.) The text of the citation describes the heroic actions which justify the medal. The details of Bennett's citation were kept secret until the day of the award. It states:

The homepage of the 14th carries photos of the award ceremony, showing President Nixon with the Gray-Bennett family. ("1st Battalion, 14th Infantry: Vietnam: Medal of Honor: Bennett, Thomas W.," accessed 26 March 2018, http://1-14th.com/MOH/MOH_Bennett.html.)

Over time, Thomas Bennett's ideas, life, and courage inspired others, and the communities that he touched in his lifetime found ways to honor him and remember him. At West Virginia University, a dormitory was named Bennett Tower. The West Virginia legislature named a bridge that crosses the Monongahela River on Route 79 for Thomas Bennett. A healthcare clinic at Fort Sam Houston was named for Thomas Bennett. The ecumenical house on Oakland Street in Morgantown was also named for him, then called Bennett House. His name is on a plaque that names the veterans who were students at Morgantown High School and died in service. A barracks in Virginia also bears his name, and another in Hawaii. A photo of him hangs in the Hall of Heroes in the Pentagon, along with those of others who've been awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

In 2000, the family of Thomas William Bennett donated his Congressional Medal of Honor to the university. The medal is displayed in a case on the second floor of the old section of Wise Library, along with other materials representing his life, including McKeown's book, the citation for the Congressional Medal of Honor, and the after action report that describe the events leading up to his death. The medal is displayed on weekdays, from 8:30 a.m. until 4:30 p.m. A library employee places the medal in the case every weekday and retrieves it for safekeeping every weekday afternoon.

Article prepared by Cynthia Mullens

December 2017

West Virginia Archives and History welcomes any additional information that can be provided about these veterans, including photographs, family names, letters and other relevant personal history.