Remember...

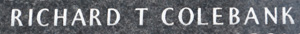

Richard Theodore Colebank

1923-1943

"The only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-Boat peril."

Winston Churchill

|

Remember...Richard Theodore Colebank

|

Richard Theodore Colebank was born to Eugenia Bumgartner Colebank and William Colebank on June 28, 1923, in Taylor County, West Virginia. The 1930 Federal Census taker recorded that Mr. Colebank was a brakeman for a steam railroad company, living in Blueville. Mrs. Colebank wasn't working outside the home. There were three young children in the home in 1930: William, 8; Richard, 6; and Albert, 3 .

In 1940, according to the census record, the family was living in the Knottsville District, so they had apparently moved in the preceding five years. They'd been living there since at least 1935, according to the census "last residence" column. Theodore [Richard] and Albert were still in the home, but William was no longer there. Mr. Colebank was a laborer on a Works Progress Administration (WPA) project. Richard was 17. Though named Richard, he was known by the nickname "Teddy" based on his middle name. ("Parents of Teddy Colebank Receive Son's Honor Award, Purple Heart Award Posthumously for Death in Action," Grafton [WV] Sentinel, 20 July 1944, p. 6.)

The Grafton Sentinel article goes on to say that while in school, Teddy was a builder of model airplanes. He was known as a local and state leader in the hobby of airplane building and had won top honors often in competition at the local and state level. In 1942, Teddy Colebank graduated from Grafton High School. Enlistment into the military followed not long after on June 30, 1942. Teddy Colebank became Seaman First Class Richard T. Colebank of the U.S. Navy.

According to the Grafton Sentinel article, the ship that Richard Colebank was on was broken into two pieces and "sank immediately in heavy seas." Therefore, it is likely the ship on which Richard Colebank served was not the USS Granville but rather a Finnish ship, at one time called Tabarka, that had been seized by the U.S. government in Norfolk and registered as Panamanian steam merchant ship Granville. ("Granville: Panamanian Steam Merchant," Uboat.net, accessed 14 February 2018, https://uboat.net/allies/merchants/ship/2784.html.) This ship was sunk on March 17 in the North Atlantic. There were U.S. Navy personnel on board, but the personnel known to have been on board and listed on the site referenced were mostly merchant marines from the U.S., Spain, the Netherlands, Finland, Estonia, and Malta. ("Granville: Panamanian Steam Merchant [crew list]," Uboat.net, accessed 14 February 2018, http://uboat.net/allies/merchants/crews/ship2784.html.) Thirty-four men survived the attack and thirteen died. The ship is thought to have been sunk by German submarine U-338, which sank four ships and damaged a fifth, and which reported for the last time in September 1943. The fate of the U-338 is not known. ("U-338," Uboat.net, accessed 14 February 2018, http://uboat.net/boats/u338.htm.)

According to the site "Granville: Panamanian Steam Merchant,"

At 14.52 hours on 17 March 1943, U-338 fired torpedoes at the convoy SC-122, observed one hit and heard three detonations which were probably depth charges.The Granville (Master Friedrich Matzen) was struck by one torpedo on the port side at the #2 hatch, starting a fire in the hold. The engine room flooded as the watertight door between the coal bunkers and fireroom was open, because coal was being transferred from the bunkers to the fireroom. Ten crew members working in the engine room were killed. The vessel broke in two amidships and sank within 15 minutes, taking two armed guards with her. The surviving men of her complement of 35 crew members, eleven armed guards and one passenger (an US Army Lt Col) abandoned ship in lifeboats and rafts. The survivors, including the master, were picked up about an hour later by HMS Lavender (K 60) (Lt L.G. Pilcher, RNR) and landed at Liverpool on 23 March. The second mate was rescued but died of wounds on the corvette and was buried at sea.

The merchant marines or merchant fleet is a "a force of civilian mariners to haul vital military cargo overseas in a national emergency." (William Geroux, "World War II Shows Why We Need the Merchant Marine," 21 April 2016, Time.com, accessed 14 February 2018, http://time.com/4303121/world-war-ii-merchant-marine.) The merchant marines risked their lives to carry necessary support equipment, food, and other supplies to Allied forces. When America entered the war, the supply line was an attractive and necessary target.

Even before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, American merchant mariners on freighters and tankers flying the U.S. flag were risking their lives to carry arms, ammunition and food to keep the British in the fight. When America formally entered the war, German U-boats invaded U.S. waters to cut off the supply line at its source. They sank American cargo ships within sight of tourist beaches in Virginia and Florida, and at the mouth of the Mississippi River. They torpedoed ships and killed mariners in the Arctic, the South Atlantic, the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico and the Mediterranean. They sank hundreds of vessels, killed more than 9,000 American merchant mariners, and sent tons of vital supplies to the sea bottom.The U.S. military was unprepared for the U-boat onslaught, and for much of 1942 it lacked the ships, planes and, sadly, the inclination to protect the cargo ships. Again and again merchant mariners were sent on hazardous voyages with no protection, in the hope they would be lucky enough not to encounter a U-boat. The result was a slaughter that the government did its best to downplay and conceal from the public. (Geroux)

The Granville carried "3700 tons British and American military stores, 500 bags US mail and an invasion barge as deck cargo." ("Granville: Panamanian Steam Merchant," Uboat.net, accessed 14 February 2018, https://uboat.net/allies/merchants/ship/2784.html.)

One in twenty-six mariners aboard merchant ships died in the line of duty. The percentage of deaths and high casualty rate were kept secret during the war in order to attract and keep mariners at sea. The merchant marines suffered a higher death rate than any other U.S. service. During 1940-1942, U-boats sank more ships than were being built for Allied forces. During 1942, between 1,200 and1,664 ships were sunk, 1,097 of them in the North Atlantic. Inexplicably, the U.S. took no action to protect the ships by arming them, providing cover, or organizing convoys. The ships were sometimes attacked so close to U.S. shores that U.S. beaches were the sites of natural collection of burned out ships and bodies. Not until 1942 did the U.S. begin ordering blackouts of coastal cities to reduce the outline of U.S. ships against bright lights on the horizon, which made the ships so easy to see. ("U.S. Merchant Marine in World War II," accessed 14 February 2018, http://www.usmm.org/ww2.html.)

This site goes on to say that the March 1943 attack was the "greatest convoy battle of all time" because "88 merchant ships and 15 escorts, were bound for Europe from New York, via Halifax, on parallel courses. In mid-Atlantic, they were relentlessly attacked by 45 U-Boats operating individually and in 'wolfpacks,' who fired 90 torpedoes, sinking 22 ships, and resulting in 372 dead."

Given the statistics, one must conclude that service aboard the merchant marine fleet in the North Atlantic was among the most dangerous, if not the most dangerous, duty that an enlistee could be assigned. It was also among the most necessary. Again, from the site "U.S. Merchant Marine in World War II":

One way to understand the Second World War is to appreciate the critical role of merchant shipping...the availability or non-availability of merchant shipping determined what the Allies could or could not do militarily...when sinkings of Allied merchant vessels exceeded production, when slow turnarounds, convoy delays, roundabout routing, and long voyages taxed transport severely, or when the cross-Channel invasion planned for 1942 had to be postponed for many months for reasons which included insufficient shipping....Had these ships not been produced, the war would have been in all likelihood prolonged many months, if not years. Some argue the Allies would have lost as there would not have existed the means to carry the personnel, supplies, and equipment needed by the combined Allies to defeat the Axis powers. [It took 7 to 15 tons of supplies to support one soldier for one year.] The U.S. wartime merchant fleet.constituted one of the most significant contributions made by any nation to the eventual winning of the Second World War....

The Navy, in accordance with wartime protocol, waited a year before declaring S1c Colebank dead. By that time, William Colebank, his brother, was a chief warrant officer of the Armored Command in Fort Knox, Kentucky, and younger brother, Albert, was awaiting his eighteenth birthday before entering the Army Air Corps. ("'Teddy' Colebank Officially Listed as Missing in Action: Went Down with Ship in North Atlantic on March 17, 1943," Grafton News, 31 March 1944, p. 1.)

A year after the sinking of his ship, many memorials were held for Richard Colebank in St. Paul Methodist Church in Grafton. Photos of the Colebank family and more information about them appear on a family history page ("William Allen Colebank," accessed 21 February 2018, http://www.thecolebankfamily.com/William_Allen_Colebank.html) and on Find A Grave.

Though his service life was short, there is no doubt that Richard Colebank's contributions to the war effort through the Navy and merchant marines was a legacy that cannot be diminished with time.

Article prepared by Cynthia Mullens

August 2017

West Virginia Archives and History welcomes any additional information that can be provided about these veterans, including photographs, family names, letters and other relevant personal history.