Charleston Gazette, February 14, 1945

Remember...

Harry Isadore Silverstein

1894-1945

"I must study politics and war that my sons may have liberty to study mathematics and philosophy."

John Adams

Charleston Gazette, February 14, 1945 |

Remember...Harry Isadore Silverstein

|

In no arena did John Adams' quote play out more decisively than in World War II, when Army Lieutenant Colonel Harry Isadore Silverstein met his death while the U.S. was engaged in a war that ironically involved both him and his son. At the outbreak of World War II, Harry was 47 years old. He had seen service in the U.S. Navy in World War I. The steel company in which he was an executive evolved from his family's scrap metal business and would become a supplier to the armament industry for the duration of the war. On all conditions, he would not have had to take up arms. Yet he enlisted.

Depending on which Federal Census one is to believe (1920 or 1930), Alexander and Lena were born in Russia or Poland. A Find A Grave memorial (#91619769), however, lists the birthplace of both as Lithuania. Harry Silverstein's daughter Lois Silverstein Kaufman has a plausible explanation for the discrepancy: The area from which they emigrated changed hands from principality to principality, so depending on the time frame, those being enumerated might claim any one of these places as their homeland. Lois believes that their native town was Kovno (now Kaunas) in Lithuania. Harry was the eldest of three brothers; Sam came along in 1896, and Joseph, in 1898. Later the family would add two sisters: Bertha and Tressa.

Educated in the schools of Charleston, Harry became involved in the family metal business, A. P. Silverstein and Sons, at a young age. He terminated his formal education after tenth grade because he was needed to work and help with the education of his younger siblings. He was the only one of his family who did not go to college, but he was a self-educated man, a fact which his early business success can attest to.

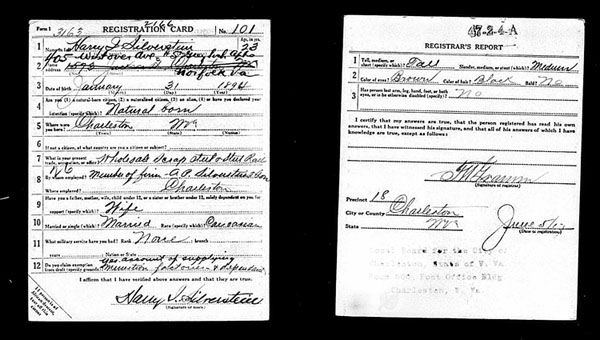

Harry registered for the World War I draft on June 5, 1917. Rather than serve in the Army, he enrolled at the Navy Yard in Washington, D. C., on December 12, 1917, and became a storekeeper. He served at HQ 5th Naval District in Norfolk, Virginia, from December 14 through March 4, 1918; at HQ 3rd Naval District, New York City from March 4 through September 9, 1918; and at Naval Training, Camp Pelham Bay Park, New York, from September 9 through November 11, 1918. He was discharged from Pelham Bay Park on December 12, 1918.

World War I draft registration card. National Archives and Records Administration

In 1916 he had married Florence Jordan, and, after the war, they became parents of three children: Marion, Lois, and Philip. The young family settled in at Charleston, and newspaper accounts of his death emphasize his involvement in the community. At the time of his enlistment in the Army for World War II, he was president of the Midwest Steel Corporation. Nevertheless, he found time to promote music and the arts. Both Florence and Harry were music lovers, as well as musicians. Florence had aspired to go to the Cincinnati College Conservatory of Music, but her family could not afford for her to go. Like others of her era, however, that did not stop her from engaging in what she loved, and she gave piano lessons privately. Lois, who took her bachelor's degree in music, says her mother was her first piano teacher. Harry was a violinist who participated in a local string quartet that practiced at the Silverstein home. One aspect of Harry's life the family is most proud of is his promotion of serious music to the community. During his tenure on City Council, he was instrumental in the building of the Charleston Municipal Auditorium, and that edifice became the ultimate venue for Community Music Association concerts. Harry was the first president of CMA, and he stayed in that capacity until his World War II service ended it. Concerts were gala affairs, and they included outstanding classical performances of the time, such as Jos Iturbi.

In addition to his years on city council, he served on the Board of Directors of the Salvation Army and helped establish the Salvation Army Military Club on Kanawha Boulevard. In short, Harry I. Silverstein was a "pillar of the community." There were many reasons why he would not have had to serve in the military in World War II. Yet he enlisted.

After his enlistment in August 1943, Lt. Col. Silverstein was stationed in Washington, D.C. His role in D.C. with the Army was to advise on the use of scrap metal:his experience would have made him the nation's expert. He did not anticipate going to Europe, but when he learned that Phil was injured in the Battle of the Bulge (for which he received a Purple Heart) and was recuperating in an English hospital, Harry requested a tour in Europe. He had been in Europe only two weeks prior to his death on February 7, 1945, and had just completed a tour of France. In one of the many ironies of war, Harry died of a heart attack. Though wounded, Phil survived the war relatively unscathed and describes his battle experiences in a January 2, 1945, letter to brother-in-law Carl and sister Marion Lehman in a lighthearted manner:

I presume that William Jeffrey is coming along fine and that the two of you are going through the rigors of housebreaking Wallie, a job which I am sure I would not like.This morning the medics gave me the purple heart which is a riot. An 88 hit just behind me yesterday while I was walking back from breakfast. All it did was sting me in the seat and elbow. One small piece drew blood in that embarrassing spot so now I have the purple heart.

I think of myself as the hard luck kid. I have had blister on my heel which I have to have dressed daily, one hell of a cough, and my fingers won't thaw out from the first joint to the tips. [They're] just numb with no feeling.

Everyone else is in the same boat so I have nothing to cry about.

Gee but how I hate winter weather, I'm getting just like an old man. I'm seriously thinking of staying in California when the war is over and live a nice peaceful easy going life.

Carl, when that boy of yours begins to learn to walk which of course won't be for some time, please don't let him start off with the left foot.

Nothing much else to add. I guess this has been pretty dull.

Love

Phil

Much of what we know regarding Harry's death is the result of Phil's meticulous documentation of his remembrances of that period of time, both in letters and journals. A lengthy March 10 letter to his mother and Lois in his impeccable handwriting depicts a dramatic shift in mood, as he writes with seriousness and poignancy:

Major Harry R. Grau, clearly a dear friend of Harry, was determined to be of assistance and comfort to the family, and on February 26, he wrote a ten-page letter to Florence "and girls." He included a sketch of the Cambridge American Cemetery. He starts with an explanation of why his writing has been delayed:

I just received a letter from Lois, & noting that the news of Harry's death is now officially [known], I'm free to write you the details as completely as they are known to me. Army censorship precluded my writing before March 7th, but the circumstances now present in so far as you are concerned no longer necessitate application of that rule. I appreciate how desirous it is for you to know as much as you can, so I shall set down the facts in as chronological and clear a fashion as is possible.

Grau continues with the exact circumstances in great detail:

On Tuesday, Feb. 6th, at approximately 3 [o'clock] in the afternoon, a trunk call came in for me from Col. Silverstein's office in London. He had just arrived from Paris & hadn't even taken his coat off when he put the call through. Florence, you can imagine our mutual enjoyment & happiness in talking with one another. He was in excellent spirits and spoke to me of his immediate plans. He was leaving the following morning to see Phil, and was returning to London on Thursday. We made arrangements to get in touch with one another on Thursday to insure a meeting over the week-end in London. With that happy note we said good-bye & I made application for pass over the week-end. I was keyed up and excited, Florence, in knowing Harry was so close & how soon I would be seeing him. How far was the tragedy of our actual meeting from the expectation that was in mind only I alone do know.

Grau then recounts how he received a call on the morning of February 8 from Phil, informing him that Harry had had a heart attack. He first asserts his disbelief, which then turns to shock. Soon, though, he assumes the responsibility for Harry's funeral. He mentions that Phil felt his father did not look well and tried to persuade him to stay overnight, which Harry declined to do because of his need to be present at War Ministry meetings the following day. Grau goes on:

Harry boarded a train at Great Malvern around 6 that evening, Wednesday, the 7th. He was in a first class compartment with a number of civilians and around 8 o'clock was approaching the town of Evesham, some 20 or 30 miles southeast by east of Great Malvern. Suddenly, he clutched his heart, groaned once and slumped in his seat, dead. A civilian doctor on the train was called to his side almost at once but there was nothing that could be done. The body was removed from the train, taken back to Great Malvern, & Phil notified..Certain secret papers in Harry's possession had to be picked up & at the same time his personal effects were inventoried by Phil & Major Stevens. The disposition of his London effects was handled by his office who assured me that they would be handled most meticuously and exactly.

Harry's burial was scheduled for Tuesday, February 13, at 3 p.m. at the American Cemetery in Cambridge. Grau got in touch with Rabbi Mortimer Fierman of Cleveland and Cincinnati to conduct the services. He met Phil and Major Stevens in the cemetery office. He describes the day as "sharp but not too cold. The sky hung low and leaden, with a cloud covered sun trying to gleam through, & being only partially successful." Grau then describes the thirty individuals who were to be buried that day, noting that the funeral party was made up of between two and three hundred officers and men. After the names of those being buried were read, the Catholic portion of the service began, followed by the Jewish, and then the Protestant. After the religious ceremonies came the military rites: The bugler played taps, and the firing party rendered their volleys. Grau continues:

Much of the information herein is taken from documents and letters in the Phil Silverstein Collection at the West Virginia Archives (Ms 2015-067), courtesy Jane Silverstein. Additional family information provided by Harry's daughter, Lois Silverstein Kaufman.

Article prepared by Patricia Richards McClure

December 2016

West Virginia Archives and History welcomes any additional information that can be provided about these veterans, including photographs, family names, letters and other relevant personal history.